MMØDGR/p will be operating from the Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve (GMFF-046) on Saturday, 6th February, 2010.

The portable station will be located at the Shore Wood (southeast corner of Loch Lomond). Equipment: Icom IC-706MKIIG with HLA-300 Plus (300W) HF Power Amplifier. Antenna: 9m high Vertical with CG-5000 Automatic Antenna Coupler.

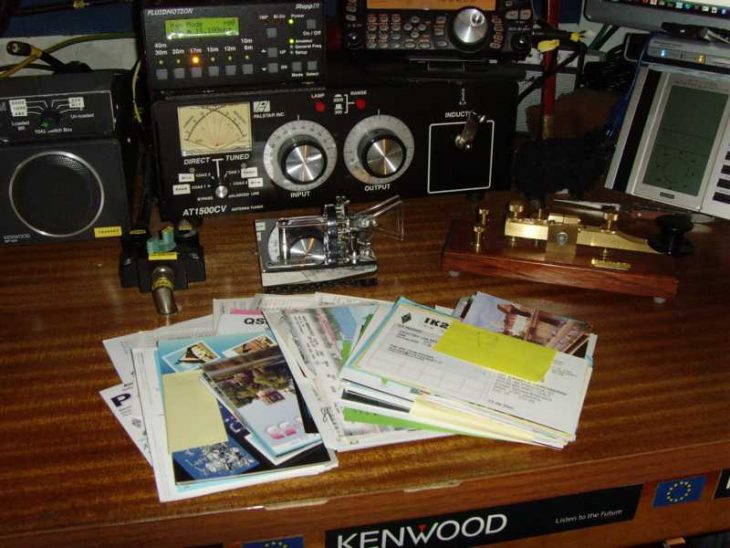

Grid locator IO76RB, WAB NS48, EU Area SC31 (West Dunbartonshire), IOTA EU-005. Bands, modes and frequencies ± QRM: 20 m (BPSK63 14.072 MHz, CW 14.044 MHz, SSB 14.244 MHz); 30 m (BPSK63 10.142 MHz, CW 10.110 MHz); 40 m (BPSK63 7.044 MHz, CW 7.014 MHz, SSB 7.144 MHz). QSL-cards via MMØDFV (preferably RSGB QSL-bureau).

Loch Lomond National Nature Reserve (GMFF-046) lies in the southeast corner of Loch Lomond, in the southern part of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park (GMFF-002). This portable expedition gives you two WFF reference numbers GMFF-046 and GMFF-002 simultaneously. The Reserve includes some of the woodlands for which Loch Lomond is renowned, including the wooded shores on the mainland and on the islands of Inchcailloch, Clairinsh, Torrinch, Creinch and Aber Isle and the wetlands at the mouth of the River Endrick.

Detailed information & map are available at http://www.srars.org/wff-reports/gmff-046.htm

News received this morning is that the Northern Cross Rally 2010 held in Wakefield has been cancelled, the event no longer taking place on the 14th February as previously circulated. It is suggested it may take place later this Year with the month of June being a possibility.

The event is run by the Wakefield & District Radio Society and in recent Years has moved from the old QTH at the Thornes Sports Stadium Wakefield to a new location ¾ mile south of Ossett town centre, in the grounds of Ossett School, on Storrs Hill Road, Ossett, Wakefield in West Yorkshire.

It is disappointing to hear it is cancelled but should you require further information please contact their Secretary David Lockwood G4CLY.

73 de Charles………

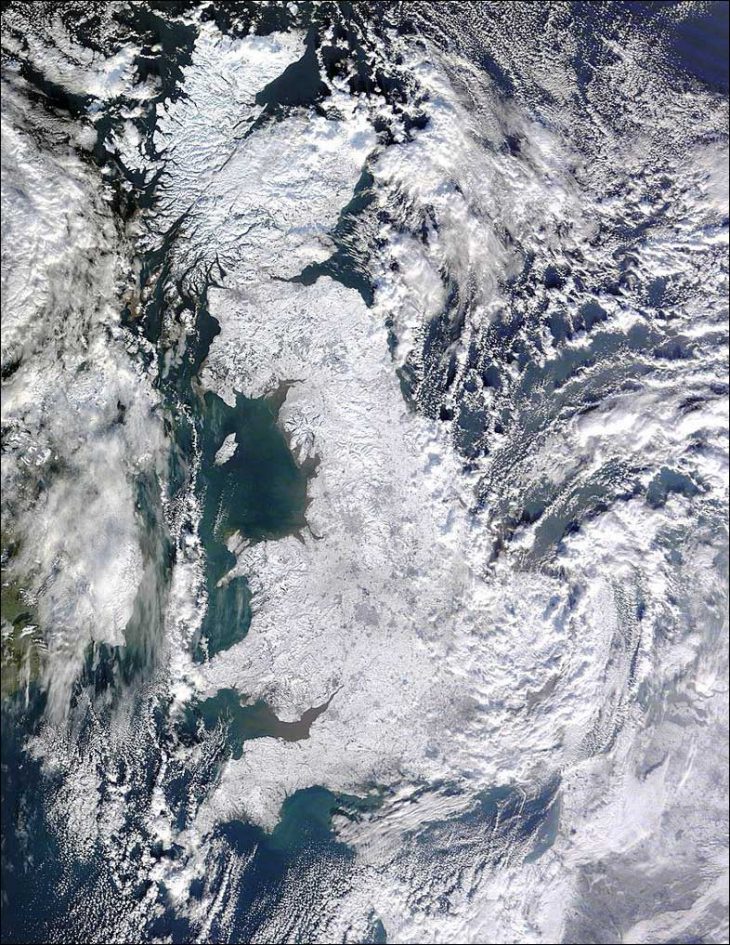

This page will shine the spotlight on recent and maybe unusual weather events that occur in the UK. Several of them will have been covered in the Blog but it may show some interesting aspects that the good old UK weather has to throw at us. Cartainly from my QTH we have noticed a remarkable turn around in Winter weather from how it was in the late 60’s and early 70’s for example. Please call back as i work on this page of the site.

Thanks, Charles

It is also the most accessible offshore island in the Gulf, due to regular passenger and car ferry services and some air links. This island is famous for its world-class wineries and thriving art scene.  You’ll find sandy swimming beaches, dramatic coastal walks and scenery, and a great selection of accommodation, restaurants, cafés and wineries. Waiheke has also become renowned for its international award-winning wines and its Easter Jazz Festival, which attracts musicians and followers from all over the world.

You’ll find sandy swimming beaches, dramatic coastal walks and scenery, and a great selection of accommodation, restaurants, cafés and wineries. Waiheke has also become renowned for its international award-winning wines and its Easter Jazz Festival, which attracts musicians and followers from all over the world.

During World War II, three gun emplacements were built on the eastern edge of Waiheke to protect Allied shipping in Waitemata Harbour, in the fear that Japanese ships might reach all the way to New Zealand. This mirrored developments at North Head and Rangitoto Island. The guns were never fired in anger. The empty emplacements and the extensive tunnels below them which now give a very interesting tourist attraction for the Island.

Waiheke Island was the first community in New Zealand to vote for a nuclear free zone and this action is said to have contributed to the national decision to become nuclear-free under David Lange‘s government. This assertion was made by a prior community board member, and requires further confirmation.

In 1999 Waiheke’s community board voted Waiheke as a ‘genetic engineering free zone’ but this is a matter of principle rather than fact, as only national government controls exist over genetically engineered foods and grains.

Thanks again Warren, hope to hear you again in the near future!

73 de Charles…

(tnx Wilkpedia & tourismwaiheke for info)

The National Grid has issued its second gas alert in three days, with demand expected to hit a new record of 454 million cubic metres yesterday. A spokeswoman said technical problems had led to a supply shortfall of 52 million cubic metres  from the Langeled pipeline, which takes gas from Norway. National Grid said other suppliers were putting more gas into the network and major customers were cutting back on usage in response to the alert.

from the Langeled pipeline, which takes gas from Norway. National Grid said other suppliers were putting more gas into the network and major customers were cutting back on usage in response to the alert.

About 4,000 homes across southern England are without electricity because of trees falling on power lines and safety mechanisms being triggered by ice weighing down cables and Air Sea rescue services have also been very busy. Up to 40,000 homes across Britain have been similarly affected since Wednesday. Budget airline Easyjet has cancelled nearly 90 flights on Thursday, mostly at Gatwick where a total of 147 inbound and outbound flights were scrapped. British Airways has also cancelled some flights. On the railways, 20 operators’ services are disrupted. East Coast has advised passengers not to travel between Perth and Inverness. Virgin Trains has cancelled several services between London and both Manchester and Birmingham. A teenage boy died and his mother was seriously injured when they were hit by a lorry after leaving a car that had crashed on the A1 in North Yorkshire near Scotch Corner on Wednesday night. A 42-year-old man died further along the road when his car crashed with a lorry south of Cockburnspath in Berwickshire. In Aberdeenshire, a man was treated in hospital after being injured when the weight of snow caused a cattle shed to collapse on Thursday morning. Meanwhile, a search has begun in Glen Affric in the Highlands for a 40-year-old man and a boy, 15, who have not been heard from for two days.

Flora Fauna :-

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) is organising emergency feeding of several threatened species, including bitterns and cirl buntings. The RSPB is also asking people to feed garden birds,  which are struggling to find food in the freezing weather. The harsh winter could hit bird numbers “for many years to come”, they warn. “The extremely hard winter spanning 1962 and 1963 was arguably the single event that had the greatest impact on wildlife within living memory,” said Mark Avery, the RSPB’s conservation director. “With the icy weather predicted to last at least another week, this winter could be the single greatest wildlife killer of the new millennium.”

which are struggling to find food in the freezing weather. The harsh winter could hit bird numbers “for many years to come”, they warn. “The extremely hard winter spanning 1962 and 1963 was arguably the single event that had the greatest impact on wildlife within living memory,” said Mark Avery, the RSPB’s conservation director. “With the icy weather predicted to last at least another week, this winter could be the single greatest wildlife killer of the new millennium.”

The birds are finding it difficult to catch fish in ice-locked wetland areas. The society says that it is being inundated with calls from the public, who are reporting unusual visitors to bird feeders in gardens – including woodcock, snipe and grey wagtails. The freezing weather means that gardens have become havens for wildlife, it adds, as birds and animals are forced to venture further afield in the search of food. The RSPB has joined forces with other conservation groups – including Natural England, the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust – to urge people not to disturb flocks of wetlands birds. They say ducks, swans, geese and other wading birds cannot afford to waste energy that they cannot readily replace.

Local authorities are battling to keep major routes clear as gritting salt is rationed and the big freeze continues.The Local  Government Association said major roads would be gritted and people would still be able to “get around”. Local authorities have agreed to cut salt use by 25% in an attempt to preserve dwindling supplies. The Highways Agency has already stopped treating motorway hard shoulders in England and the government has ordered salt from abroad but this is not due to arrive until 21 January. The AA was surprised councils had agreed to cut the amount of salt they were using, as it was already being mixed with grit to try and extend its reach. “The roads we come to expect to be safe may no longer be safe, and I think people need to know which roads are and which roads aren’t going to be treated any more so that we can at least have an indication where our journey are going to be hazardous and maybe delayed.”

Government Association said major roads would be gritted and people would still be able to “get around”. Local authorities have agreed to cut salt use by 25% in an attempt to preserve dwindling supplies. The Highways Agency has already stopped treating motorway hard shoulders in England and the government has ordered salt from abroad but this is not due to arrive until 21 January. The AA was surprised councils had agreed to cut the amount of salt they were using, as it was already being mixed with grit to try and extend its reach. “The roads we come to expect to be safe may no longer be safe, and I think people need to know which roads are and which roads aren’t going to be treated any more so that we can at least have an indication where our journey are going to be hazardous and maybe delayed.”

Some are saying is the coldest winter since 1963……is it?

That winter, the snow started on Boxing Day 1962 and the big freeze lasted until March 1963.  Blizzards caused snowdrifts up to six metres deep, telephone lines were brought down and temperatures fell so low the sea froze over. But with thousands of schools remaining shut, travel problems continuing and power cuts affecting thousands of homes, how different is it in 2010?

Blizzards caused snowdrifts up to six metres deep, telephone lines were brought down and temperatures fell so low the sea froze over. But with thousands of schools remaining shut, travel problems continuing and power cuts affecting thousands of homes, how different is it in 2010?

Schools in ’63 :- On Wednesday about 9,000 schools were shut across England, with 950 in Wales, and at least 250 in Scotland and 16 in Northern Ireland. While some schools were forced to close in 1963, Peter Hennessy, professor of contemporary British history at Queen Mary University of London, said the large number of closures this week indicated the UK had become a “health and safety nation”. But he said people usually lived within walking distance of their schools in 1963 – while more parents and staff drive to school now – so snow on the roads has more impact on closures these days. Wading to school through inches – not centimetres – of snow is something some of us remember very well! We had no choice: “You put wellies on and walked. If you could get on a sledge, you went to school. Sledging was skiving.”

Homes in ’63 :- Thousands of homes across the UK have been affected by power cuts, often because of falling trees on power lines and ice weighing down cables. National Grid issued its second gas alert in three days – and demand was  expected to hit a new record of 454 million cubic metres. It was a very different picture in 1963. Gas and electricity was restricted, most people had no central heating and some people had to resort to collecting coal from frozen depots.

expected to hit a new record of 454 million cubic metres. It was a very different picture in 1963. Gas and electricity was restricted, most people had no central heating and some people had to resort to collecting coal from frozen depots.

A few had Agas or fuel burners but most people relied on gas fires in one room or had no fires at all. Maybe they had a water bottle to warm the bed (I still do!). Remember waking up to find the inside of my window completely iced up or a glass of water frozen solid in the bedroom?.

Everything is warmer, pipes don’t freeze outside the home because of the amount of warmth being lost from houses. In 1963, cold water tanks froze – there was a constant fear of pipes bursting. Frozen pipes affected thousands of people in 1963, with some getting drinking water from corporation carts driven round the streets. By 24 January water was being rationed in Wales, as the water board struggled to get supplies from reservoirs.

Transport in ’63 :- Freezing temperatures and icy roads have created “nightmare” road conditions in 2010 and rail services have been severely disrupted. Air travel has been beset by delays and cancellations. Many councils are limiting gritting to major roads only as salt supplies are stretched. Roads faced similar disruption in 1963, but the biggest problem was not a lack of grit – but a relentless blustering wind. Most of the country roads were impassable – the wind was horrendous. A snow plough would go down a road, but the wind kept blowing snow back on to the road and it would refill within hours – this went on week after week. There were hardly any motorways – the M1 had only opened in 1959.

Coldest Recorded Places

Vostok, Antarctica: -89.2C

Oymyakon, Russia: -71.1C

Verkhoyansk, Russia: -67.7C

Snag, Yukon, Canada: -63C

Prospect Creek, Alaska, US: -62.1C

73 de Charles……

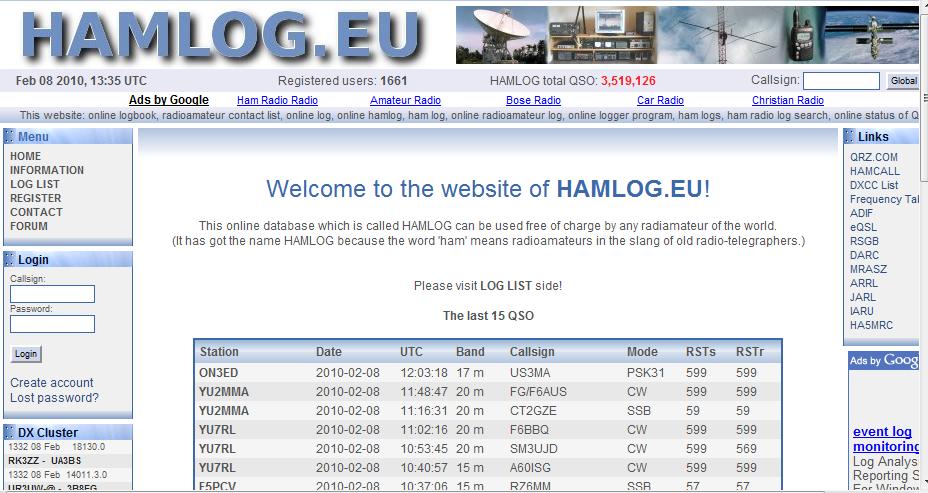

to choose and you can either search the logs directly on line or add the facility to your own website where again you personal logs can be seen. Just one example is that of ‘Hamlog EU‘.

to choose and you can either search the logs directly on line or add the facility to your own website where again you personal logs can be seen. Just one example is that of ‘Hamlog EU‘.

You’ll find sandy swimming beaches, dramatic coastal walks and scenery, and a great selection of accommodation, restaurants, cafés and wineries. Waiheke has also become renowned for its international award-winning wines and its Easter Jazz Festival, which attracts musicians and followers from all over the world.

You’ll find sandy swimming beaches, dramatic coastal walks and scenery, and a great selection of accommodation, restaurants, cafés and wineries. Waiheke has also become renowned for its international award-winning wines and its Easter Jazz Festival, which attracts musicians and followers from all over the world.

from the Langeled pipeline, which takes gas from Norway. National Grid said other suppliers were putting more gas into the network and major customers were cutting back on usage in response to the alert.

from the Langeled pipeline, which takes gas from Norway. National Grid said other suppliers were putting more gas into the network and major customers were cutting back on usage in response to the alert. which are struggling to find food in the freezing weather. The harsh winter could hit bird numbers “for many years to come”, they warn. “The extremely hard winter spanning 1962 and 1963 was arguably the single event that had the greatest impact on wildlife within living memory,” said Mark Avery, the RSPB’s conservation director. “With the icy weather predicted to last at least another week, this winter could be the single greatest wildlife killer of the new millennium.”

which are struggling to find food in the freezing weather. The harsh winter could hit bird numbers “for many years to come”, they warn. “The extremely hard winter spanning 1962 and 1963 was arguably the single event that had the greatest impact on wildlife within living memory,” said Mark Avery, the RSPB’s conservation director. “With the icy weather predicted to last at least another week, this winter could be the single greatest wildlife killer of the new millennium.”  Government Association said major roads would be gritted and people would still be able to “get around”. Local authorities have agreed to cut salt use by 25% in an attempt to preserve dwindling supplies. The Highways Agency has already stopped treating motorway hard shoulders in England and the government has ordered salt from abroad but this is not due to arrive until 21 January. The AA was surprised councils had agreed to cut the amount of salt they were using, as it was already being mixed with grit to try and extend its reach. “The roads we come to expect to be safe may no longer be safe, and I think people need to know which roads are and which roads aren’t going to be treated any more so that we can at least have an indication where our journey are going to be hazardous and maybe delayed.”

Government Association said major roads would be gritted and people would still be able to “get around”. Local authorities have agreed to cut salt use by 25% in an attempt to preserve dwindling supplies. The Highways Agency has already stopped treating motorway hard shoulders in England and the government has ordered salt from abroad but this is not due to arrive until 21 January. The AA was surprised councils had agreed to cut the amount of salt they were using, as it was already being mixed with grit to try and extend its reach. “The roads we come to expect to be safe may no longer be safe, and I think people need to know which roads are and which roads aren’t going to be treated any more so that we can at least have an indication where our journey are going to be hazardous and maybe delayed.” Blizzards caused snowdrifts up to six metres deep, telephone lines were brought down and temperatures fell so low the sea froze over. But with thousands of schools remaining shut, travel problems continuing and power cuts affecting thousands of homes, how different is it in 2010?

Blizzards caused snowdrifts up to six metres deep, telephone lines were brought down and temperatures fell so low the sea froze over. But with thousands of schools remaining shut, travel problems continuing and power cuts affecting thousands of homes, how different is it in 2010? expected to hit a new record of 454 million cubic metres. It was a very different picture in 1963. Gas and electricity was restricted, most people had no central heating and some people had to resort to collecting coal from frozen depots.

expected to hit a new record of 454 million cubic metres. It was a very different picture in 1963. Gas and electricity was restricted, most people had no central heating and some people had to resort to collecting coal from frozen depots.